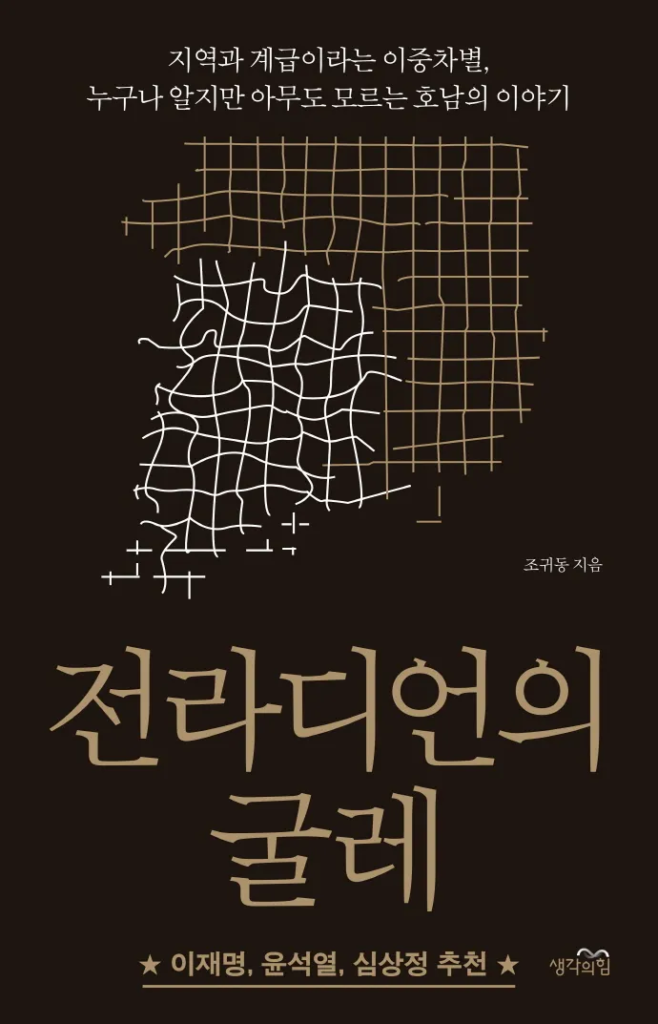

A Korean Christian man – whose wife and grandmother hail from the Jeolla-do region of southwestern South Korea – has witnessed firsthand the pain of regional discrimination. In South Korea, regional bias (called jiyeok gamjeong, or regional enmity) runs deep. Observers have noted that “if the U.S. has racism, South Korea has regionalism,” reflecting how prejudice between regions can rival racial bias in intensity(koreaexpose.com). This is especially true for Jeolla-do (often called Honam), a region with a history of political and economic marginalization. Through the story of this man’s family, we explore the historical roots of discrimination against Jeolla-do, examples of how it has impacted families in jobs and daily life, the bias that persists today, and how these experiences have shaped his Christian commitment to justice.

Historical Roots of Jeolla-do’s Marginalization

Jeolla-do’s troubles did not begin in modern times – regional rivalry in Korea dates back centuries. But in the 20th century, political events turned rivalry into entrenched discrimination. During the authoritarian presidency of Park Chung-hee (1961–1979), policies openly favored Park’s home region in the southeast (Gyeongsang or Yeongnam) at the expense of the southwest (Jeolla or Honam). Park relied heavily on fellow Yeongnam natives for elite government posts, while dissenting voices from Honam were sidelined(refworld.org). Massive industrialization projects were steered to Gyeongsang cities like Ulsan and Pohang, transforming them into booming industrial hubs, whereas Jeolla was largely left behind as a rural backwater(koreaexpose.com). Major highways and development programs bypassed Jeolla-do, exacerbating its isolation and economic underdevelopment(koreaexpose.com). This era cemented a perception that Jeolla people were being punished and excluded from the nation’s prosperity due to their region.

Political oppression compounded the economic neglect. In May 1980, during the military regime that followed Park, a pro-democracy uprising in Gwangju (the capital of South Jeolla) was brutally crushed by the army. Civilians in the city were attacked and as many as 2,000 people were killed in what came to be known as the Gwangju Massacre(refworld.org). This tragedy left an open wound in the Honam region. For Jeolla-do residents, it was a grim confirmation that they were viewed as enemies by those in power. The memories of 1980 taught families like this man’s grandmother – who lived through that time – that speaking up could be dangerous. Many in Jeolla-do turned their grief into a quiet determination to seek justice and democracy, often with the support of sympathetic church communities. It was not until much later that the nation reckoned with this injustice: years afterward, two former presidents were prosecuted for their roles in the massacre(refworld.org), and a gradual process of healing began.

Political democratization in the late 1980s and 1990s started to chip away at regional discrimination. For the first time, a native of Jeolla-do, Kim Dae-jung, was elected president in 1997, signaling hope for greater inclusion. Even leaders from the rival region acknowledged past wrongs. In 2016, the chairman of the then-ruling conservative party (ironically, himself a Jeolla native) issued a formal apology for “decades of discrimination” against Honam residents(koreajoongangdaily.joins.com). “The conservative administrations in the past discriminated against Honam and hurt the Honam people’s pride… I apologize for this,” he declared(koreajoongangdaily.joins.com). Such admissions were significant – they validated what Jeolla families had long felt. Yet, an apology, however sincere, could not instantly erase generations of bias woven into society’s fabric.

Family Stories of Discrimination and Perseverance

For this man’s family, the abstract notion of regional discrimination became personal reality. His grandmother, born in a Jeolla farming village in the 1940s, grew up in a Korea where people from her region were often treated as second-class citizens. During the rapid industrial growth of the 1960s and ’70s, she saw many young people, including relatives, leave Jeolla-do in search of jobs because opportunities back home were scarce(refworld.org). She recalls neighbors whispering that companies in Seoul or Busan might quietly reject applicants from Jeolla. In fact, many Honam families migrated to other provinces or the capital seeking fair chances, as local development lagged behind(refworld.org). Those who left often hid their accents and hometowns to avoid prejudice. The grandmother’s own children faced this dilemma. When her son (the man’s father) moved to Seoul for work, he downplayed his provincial origin, fearing that hiring managers – often from the rival Yeongnam region – would pass over him if they knew. It was an open secret that one’s regional background could function like an invisible ceiling in both government and corporate careers.

The man’s wife provides a more contemporary example. She is a proud Jeolla-do native who excelled in school and attended a top university in Seoul. Yet, even in the 2000s, she encountered subtle snubs once people recognized her dialect. Classmates would jokingly mimic the Jeolla accent, a practice that stung because it echoed long-held stereotypes. (Some from the rival region derogatorily call the Jeolla speech “kkaengkkaengi,” likening its sound to a whining noise (koreaexpose.com).) In job interviews after college, she made a conscious effort to speak standard Seoul Korean, worried that a hint of her accent might tip the interviewers’ biases. Once, a senior colleague casually remarked, “Oh, you’re from Jeolla? I couldn’t tell at all!” – a comment meant as a compliment on her speech, but which revealed the underlying assumption that sounding “Jeolla” was undesirable. Such microaggressions in the workplace accumulated over time. She noticed that among colleagues of equal talent, those from Jeolla seemed to advance slower unless they had shed all markers of their origin. While hard to prove and seldom overt, the pattern was painfully clear to those who experienced it.

These family stories mirror countless others. Jeolla-do parents have advised their children to “blend in” outside the region, hoping to shield them from discrimination. Workers from Honam often felt they had to work harder to prove they were “trustworthy,” battling a baseless stereotype that they are somehow less loyal or capable. And yet, the family’s faith gave them resilience. The grandmother, a devout Christian, taught her children and grandchildren that “in God’s eyes, we are all equal.” She bore insults and injustices with grace, believing that prejudice was born of ignorance and that one day truth and love would prevail. The man’s wife, empowered by both her faith and her husband’s support, refused to be ashamed of her roots. She mentors younger Jeolla women in their Seoul church, encouraging them not to lose their identity to others’ bias. Their experiences in hiring and promotion – the subtle barriers and painful comments – have only strengthened the family’s resolve to advocate for fairness. They know that discrimination’s real damage is not only missed promotions or jobs, but the erosion of God-given dignity.

Enduring Bias in Modern Society

South Korea today is a vibrant democracy with greater regional equality than in the past, but old biases are far from gone. Many younger Koreans mix freely across provincial lines, especially in big cities, and overt hiring discrimination based on region is illegal. Despite this progress, the shadow of regionalism still looms in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. Recent events show how quickly dormant prejudices can resurface.

In late 2024, a tragic Jeju Air plane crash in Muan (a city in South Jeolla) illustrated how deep-seated bias can twist public discourse. As the nation mourned dozens of lives lost in the accident, a disturbing undercurrent of online commentary began blaming the tragedy on the region itself. Hateful posts appeared, suggesting that Jeolla-do somehow “deserved” such misfortune or cynically claiming locals were exploiting the disaster for compensation(asianews.network). In one instance, commenters dubbed the incident the “Muan crash,” as if to pin a stigma on the location, prompting authorities to emphasize the neutral official title for the accident(asianews.network). Social media platforms had to delete numerous derogatory comments targeting the victims’ families, simply because the accident happened on Jeolla soil. At a memorial rally in Seoul, participants put up handwritten notes expressing condolences and anger at the spread of hate(asianews.network). The colorful mosaic of sticky notes (as seen above) spoke to a desire for unity and empathy, yet the very need for such a display was a sobering reminder that regional discrimination still rears its head, even in moments of national grief.

Indeed, South Korea has “a long history of regionalism, particularly between the Jeolla and Gyeongsang provinces,” and remnants of that history persist(asianews.network). This bias manifests in different forms today, for example:

- Hate speech in online communities: On extremist internet forums, slurs against Jeolla-do are common. The far-right website Ilbe is infamous for derogatory names like “hongeo” (fermented skate fish) to malign people from Jeolla(en.wikipedia.org). What outsiders see as a regional delicacy is twisted into a dehumanizing label. Such online hate speech has a real impact – it normalizes prejudice among young netizens and spills into offline attitudes. The National Human Rights Commission in Korea has cited hate posts against Jeolla residents (even the victims of the 1980 Gwangju Uprising) as a serious social problem(hurights.or.jp).

- Bias in everyday language and media: Casual jokes and offhand remarks sometimes still reflect anti-Jeolla sentiment. It’s not unusual to hear someone use “Jeollanomics” to imply backwardness, or to see negative stereotypes in media. Even in politics, regional dog-whistles occur; for instance, allegations that a policy favoring Jeolla is “reverse discrimination” can quickly surface, reflecting an ingrained belief that Honam is perpetually an outsider. While open discrimination is no longer accepted publicly, these subtle cues show that many minds have yet to change.

Such expressions of bias indicate that regional reconciliation in Korea remains a work in progress. At the same time, there are positive signs: civil society groups and even some churches have initiated inter-regional exchanges and dialogues, younger generations are intermarrying across regional lines (as in the case of this man and his wife), and the national media has started highlighting regional discrimination as an issue of public concern rather than ignoring it. The fact that prejudice still exists does not mean it is as strong as before – it means the struggle to uproot it must continue.

Faith, Imago Dei, and the Call to Justice

For this Korean Christian, these injustices against his family and region have become more than social problems – they are spiritual and theological challenges. His faith teaches him that every person is created in the Imago Dei (image of God), endowed with inherent worth and dignity. Thus, the prejudice that says a person is “less than” simply because of their regional origin is, in his view, an affront to God’s creation. He often reflects on Genesis 1:27, imagining God imprinting the divine image equally on a child from Jeolla’s rice paddies and one from Seoul’s high-rises alike. This conviction has moved him to confront regional discrimination not with bitterness, but with a righteous anger tempered by hope. In church gatherings, he gently reminds fellow believers that mocking someone’s accent or background is no light matter but a denial of that person’s God-given value. After all, as the Apostle James warned, “with the tongue we curse human beings, who have been made in God’s likeness” – such cursing ought not to be (James 3:9-10).

His personal journey has also brought new depth to his understanding of biblical justice. The well-known verse Micah 6:8 – “What does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.” – is no longer an abstract ideal to him, but a direct call to action. Act justly: for him, this means working to dismantle unjust structures and attitudes, including the regional favoritism that has plagued his homeland. It means speaking truth even when it’s uncomfortable, such as calling out a friend’s prejudice or challenging his church to be more inclusive. Love mercy: he believes mercy involves empathizing with those who suffer prejudice and forgiving those who perpetuate it, while striving for their hearts to change. He remembers how his grandmother, despite all she endured, prayed not only for the oppressed but also for the oppressors, echoing Jesus’s command to “love your enemies.” Her merciful spirit inspires him to approach activism with love at the core. Walk humbly with God: ultimately, he seeks to ground his quest for justice in humility, recognizing that pride and hatred can infect anyone. He regularly asks God to check his own heart – to remove any bitterness so that righteous anger doesn’t turn into the very hatred he stands against.

Crucially, this man sees the Christian church as having a pivotal role in healing the wounds of regional division. The church in Korea has historically been a force for social justice at times – from advocating for democracy in the 1980s to running ministries for the poor and marginalized. He believes the church must also lead in breaking down regional oppression. In sermons and Bible studies, he emphasizes scriptures that envision unity among diverse peoples, such as Galatians 3:28 which proclaims that in Christ “there is neither Jew nor Gentile” – and by extension, neither Gyeongsang nor Jeolla. The early church brought together people from different tribes and languages into one family; why should the Korean church not do the same for people of different provinces? He challenges his congregation to intentionally foster fellowship across regional lines. This could mean partnership programs between churches in Seoul and churches in Gwangju, or simply creating safe spaces where people can share their experiences of discrimination. The man has even organized small group trips for Seoul-based young adults (many of whom have no personal ties to Jeolla) to visit his wife’s hometown in Jeolla-do. There, they not only enjoy the famed Jeolla hospitality and cuisine but also hear stories from local Christians about the prejudice they’ve overcome. Such encounters have been eye-opening and heart-softening.

From a theological standpoint, he argues that the gospel itself demands a stance against all forms of oppression. Just as the church speaks out against racism or sexism as sins, so too regional discrimination must be named a sin – a distortion of God’s desire for human community. This conviction has given him a prophetic voice. He gently reminds his fellow believers that one cannot worship a God of justice on Sunday and laugh at bigoted jokes on Monday. He points to Christ’s example of honoring the despised (like Samaritans, who in biblical times were victims of a kind of regional prejudice) as the model for how Christians in Korea should treat those from Jeolla or any other marginalized area. In this light, advocating for regional justice is not a political pastime but a holy mandate.

Ultimately, the experiences of this man and his family have woven together into a profound theological vision: a vision of the church as a reconciling body that stands with the oppressed, and of society transformed by the recognition that every person, whether from north, south, east, or west, bears the image of God. The road to that vision is long and often uphill. Yet, he remains hopeful. Each time he prays the Lord’s Prayer, “Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven,” he imagines a bit of that kingdom coming to South Korea – a kingdom without hateful regional labels, without prejudice in hiring, without families having to worry that their background will limit their future. It looks a lot like a diverse family of God’s children dining at one table.

In sharing his story on a public platform, this Korean Christian is doing exactly what he feels called to do: act justly by shedding light on injustice, love mercy by promoting understanding over revenge, and walk humbly with God by testifying that change is possible through grace. His journey from personal pain to prophetic action invites others to join in the work of dismantling regional discrimination. As his life shows, faith and justice go hand in hand. And as South Korea continues to confront the legacy of Jeolla-do discrimination, voices like his – grounded in history, lived experience, and unwavering hope in God’s promises – are helping guide the way toward a more just and loving community(koreajoongangdaily.joins.com asianews.network).

Sources: Regional history and discrimination data from The Korea Times and Refworld; recent news from The Korea Herald/Asia News Network; cultural context from Korea Exposé; apology quoted from Korea JoongAng Daily; hate speech information from Wikipedia and human rights reports. (Biblical references: Micah 6:8, Galatians 3:28, James 3:9–10)