Historical Examples of Black–Asian Christian Solidarity

Early Interracial Fellowship: Cross-racial collaboration in church contexts has deep roots. The famous 1906 Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles was led by Black, Asian, and Latino Christians together – a powerful example that “the Spirit functions in a way that white supremacy could not control,” as one pastor noted. This early Pentecostal movement demonstrated unity across racial lines in a shared faith experience.

Civil Rights Era Alliances: During the 1960s civil rights movement, Asian American Christians were not mere bystanders. In fact, the “model minority” myth was popularized in 1966 specifically to pit Asians against Black activists and downplay the need for civil rights reform. Many Asian Americans, however, “saw through the model minority myth and refused to be used in this fashion,”standing in solidarity with Black Americans’ fight for justice. A number of Asian American clergy and laity marched, advocated, and supported civil rights (even if their contributions were less publicized). For example, activists of different races – Black, Asian, Latino – jointly led the Third World Liberation Front strikes in 1968–69 to demand ethnic studies programs, a campaign rooted in the vision of racial equality. Though not an explicitly church-led movement, many participants were people of faith who carried those values into their activism.

Black–Korean Church Efforts in Los Angeles: In the early 1990s, high-profile tragedies (like the Rodney King verdict unrest and the death of Latasha Harlins) inflamed tensions between Los Angeles’ African American and Korean American communities. Ecumenical church groups stepped up to heal these divides. Notably, Black and Korean pastors formed the African American–Korean American Christian Alliance, a coalition of about 20 churches, to foster dialogue and reconciliation. These churches organized “friendship” trips that brought Black clergy to visit Korea and Korean church leaders to visit Black communities, hoping to replace misunderstanding with personal connection. Although such efforts involved relatively small groups, they symbolized the church’s role in bridge-building after the 1992 L.A. riots. First African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church of Los Angeles and local Korean Christian organizations also hosted joint services and prayer vigils as “a symbol of progress and unity” on riot anniversaries. These historical examples show that despite periods of tension, Asian and Black Christians have a legacy of coming together against injustice.

Contemporary Collaboration and Solidarity Efforts

In recent years, a new generation of Asian American Christians has become vocal in racial justice movements, often working alongside Black churches. They are moving beyond the “mono-ethnic enclaves” of their immigrant church past and intentionally choosing interracial partnerships. Below are some notable examples of this collaboration in action:

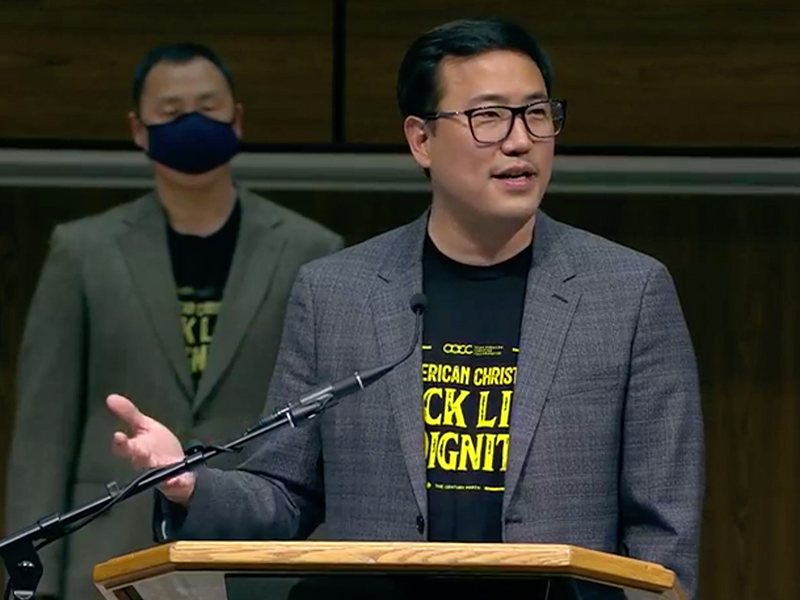

Raymond Chang, president of the Asian American Christian Collaborative, speaks at a 2021 “Black & Asian Christians United Against Racism” event in Chicago (hosted at a Black church). He emphasized that one-off events aren’t enough – “a commitment to an enduring partnership is needed” for racial justice.

- Asian American Christians for Black Lives March: In June 2020, amid the outcry over George Floyd’s murder, Asian American Christian leaders organized a march in Chicago explicitly in support of Black lives. Over 1,000 Asian American believers and allies walked from the Chinatown neighborhood across an “unspoken border” into a predominantly Black area, ending at Progressive Baptist Church (a historic Black congregation). Raymond Chang of the Asian American Christian Collaborative (AACC) called the march a “spiritual act in opposition to the powers and principalities that seek to…divide our communities,” declaring “enough is enough” to racial division. Participants came from over 100 churches – Chinese, Korean, Filipino, white, Black – rallying together in an unprecedented display of Christian solidarity. This not only surprised those who assume Asians will “keep our heads low,” but also sent a message that Asian American Christians are willing to stand publicly with their Black brothers and sisters.

- Joint Panels and Prayer Vigils: Following that momentum, Black and Asian American church leaders held public conversations to deepen understanding. In April 2021, AACC partnered with Black churches in Chicago to host a livestreamed panel “Black & Asian Christians United Against Racism.” Pastors like Rev. Otis Moss III of Trinity UCC (a prominent Black church) and Prof. Soong-Chan Rah (a Korean American theologian) discussed each community’s struggles and the need for unity. Historical links were highlighted – e.g. how 19th-century anti-Asian laws set precedents for later anti-Black laws – underscoring the “unique thread” tying their fates together. Moss noted, “Our oppression is linked together, but also our liberation is connected at the same time”. Such frank dialogues in church settings are helping Black and Asian Christians recognize common cause. On a spiritual level, leaders reminded everyone that “our battle is not against flesh and blood” (not against each other), but against the evil of racism – a fight to be waged together in both prayer and protest. Prayer vigils have likewise become spaces of cooperation: after a surge in anti-Asian violence in 2021, Asian American Christians organized “Stand for AAPI Lives & Dignity” vigils in multiple cities, where believers of all backgrounds lamented and prayed for justice.

- Mutual Support After Tragedies: Trust and solidarity are growing through mutual empathy. When a gunman killed six Asian American women in Atlanta in March 2021, many Black churches and Christian leaders reached out in compassion. Asian American theologian Gregory Lee, who belongs to a Black church, recalls how African American friends “texted, called, e-mailed, even visited our home” to express their sorrow and say, “We see you… Black folks have been there before, and we are going to stand with you now”. This kind of proactive support deeply encouraged Asian Christians, “inspiring us to keep standing up for our own community as we also stand up for others”. Likewise, Asian American Christians have been exhorting their communities to show up for Black Americans’ causes. For example, the AACC’s 2020 march explicitly declared that “what happened to George Floyd is an outrage” and that Asian believers will march alongside Black sisters and brothers against such injustice. Each community’s willingness to “mourn with those who mourn” across racial lines (Romans 12:15) has begun to build real trust.

- Church Partnerships and Pulpit Swaps: On a local level, Asian and Black congregations are forging relationships. In Seattle, Pastor Roy Chang of a Chinese heritage church opened his pulpit to Black pastors he’d developed friendships with over the years. “There’s something deeply, deeply wrong when Black people have been crying out for centuries and the church has no response,” Rev. Chang said, explaining why he invited Black clergy to speak to his majority-Asian congregation. This gesture gave Black Christian leaders a platform in an Asian church – modeling the humility and respect needed for genuine partnership. In other cities, churches have exchanged choirs, held joint Bible studies on racial justice, or teamed up for community service projects. These collaborative efforts allow Asian American Christians to tangibly serve alongside Black Christians, breaking down suspicions through shared mission. As one report noted, many younger Asian American Christians are “choosing to build stronger interracial church partnerships,” stepping beyond their comfort zones to work together for the gospel and justice.

Outcome: These contemporary examples show Asian American believers embracing a calling as reconcilers. By publicly supporting movements like Black Lives Matter and inviting Black voices into their spaces, Asian American Christians are positioning themselves as bridge-builders in historically Black and white church contexts. Over time, consistent solidarity is overturning stereotypes (such as the notion that Asians are “apathetic” or solely focused on their own issues) and instead demonstrating the biblical ideal that “if one part of the body suffers, every part suffers with it” (1 Cor 12:26). Each march, panel, and joint prayer service is a step toward the trust needed for an authentic multiracial Christian coalition.

Theological Frameworks Supporting Asian American Involvement

A robust theological foundation undergirds Asian American engagement in racial justice. Asian American Christians are drawing from Scripture and church teachings to affirm why racial solidarity is integral to their faith:

- Imago Dei – The Image of God: A core Christian belief is that all humans are made in God’s image and have inherent dignity (Genesis 1:27). This means racism is a direct affront to God’s creation. As Pastor Gabriel Catanus put it, “At a basic level, we are human beings. We bear the image of God, and God doesn’t just love human beings, He hates murder”. Violence against Black Americans or Asian Americans violates the sanctity of life. Therefore, seeking justice for any oppressed group is a way of honoring God’s image in our neighbors. Asian American Christians invoke this doctrine to remind their churches that Black lives matter to God, and thus must matter to us as well.

- Body of Christ and Biblical Unity: The New Testament teaches that the Church is one body composed of many parts (1 Corinthians 12:12–26). “If one part suffers, every part suffers with it.” Asian American believers have embraced this principle, realizing that they cannot ignore Black suffering without harming the whole body of Christ. Dallas Seminary student Andrew Wong challenged the “model minority” mentality by citing Paul’s warning against divisive philosophies: “As followers of Jesus, we must lay aside ‘hollow and deceptive’ ideologies that divide, and instead move forward in full fellowship, of one mind, in Christ Jesus”. In practice, this means rejecting any racial hierarchy and standing in solidarity as one Church family across ethnic lines. Galatians 3:28 (“there is neither Jew nor Greek…for you are all one in Christ Jesus”) is often quoted in Asian-Black dialogues, emphasizing that our primary identity is in Christ, not our race or tribe.

- The Exodus and Liberation: Asian American Christians are finding resonance with biblical narratives of liberation. Just as the Israelites commemorated their deliverance from slavery at Passover, believers today see parallels in Black Americans’ struggle for freedom. “We too should commemorate the freedom of slaves, mourn the evils of white supremacy, and commit to pursuing justice and reconciliation,” one AACC leader urged, comparing Juneteenth to an American Passover for Christians. Although Asian Americans are not direct descendants of enslaved Africans, the Exodus story invites all God’s people to remember and participate in liberative acts. This theological framing encourages Asian Americans to celebrate Black emancipation as part of God’s story – and to stand against oppression in the “mighty hand of God” that leads out of bondage. In short, the Bible’s liberation themes (from Moses to Jesus proclaiming release to the captives in Luke 4:18) provide a mandate to engage in racial justice today.

- Justice and Love of Neighbor: Scripture repeatedly calls for justice, from Old Testament prophets to Jesus’ teachings. Asian American Christians are reclaiming these themes. Jemar Tisby, a Black Christian writer, reminds us that “love for neighbor requires critiquing and dismantling unjust systems of racial oppression…if Christians claim to be concerned for their neighbors, then they must also be concerned about the structures that inhibit their neighbors’ flourishing.” Asian Americans applying this theology realize that fighting systemic racism (e.g. mass incarceration, economic inequity) is not a “political extra,” but a biblical imperative tied to the Great Commandment. They point to verses like Micah 6:8 (“do justice, love mercy, walk humbly with God”) and Isaiah 1:17 (“seek justice, correct oppression”) as marching orders. This perspective counters any notion that focusing on racial equity “distracts” from the gospel – instead, justice is presented as a core expression of Christian love.

- Reconciliation and the Cross: Theologically, Christ’s work is about reconciling people to God and to one another. Asian American believers often reference 2 Corinthians 5:18, which calls Christians to a “ministry of reconciliation.” The cross not only saves individuals but also breaks down the “dividing wall of hostility” between groups (Ephesians 2:14). For example, at the Black-Asian Christian panel, leaders cited Ephesians 6:12, reminding everyone that our struggle is against spiritual evil, not against each other. This spiritual lens helps both communities see racial injustice as a common enemy (the “powers and principalities” of racism) that they must unite to battle. The Azusa Street Revival of 1906 was lifted up as a template: it showed that when the Holy Spirit moves, people of different races are reconciled and worship together in equality. That same Spirit-led reconciliation is a theological hope for today’s church.

- Learning from Black Theology: Another significant framework is the willingness to learn from the Black church’s rich theological heritage of survival and hope. Many Asian American Christians have begun studying Black liberation theology and the Civil Rights-era church to gain insight. They see the Black church as a community that “forged the way” in responding to oppression. For instance, Asian believers facing new waves of hate are asking, “How have African Americans kept faith and fought for justice in the face of racism? What can we learn from Martin Luther King Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer, James Cone, and others?” There’s a recognition that Asian American theology of suffering (e.g. the Korean concept of han, or Japanese American reflections on internment) can connect with African American narratives of suffering and redemption. By studying Black theological perspectives on Exodus, the Cross, and the “Beloved Community,”Asian American Christians find biblical encouragement to engage in prophetic justice work themselves. In practice, this might mean incorporating gospel music, the laments of the Black church, or liberationist Biblical interpretations into Asian American church contexts to enrich and inform their approach to racial equity.

In summary, Asian American Christians are grounding their racial justice involvement in solid theological convictions – that every person is God’s beloved creation, the church must stand as one body, and the gospel demands social righteousness. These convictions give them the spiritual confidence to enter predominantly Black or White church conversations as bridge-builders who stand firmly on God’s Word.

Strategies for Building Trust and Solidarity

Engaging in racial justice within ecumenical (multi-denominational or multiethnic) church settings requires intentional effort. Asian Americans often find themselves as a minority voice in Black or White church contexts, but this position uniquely equips them to act as peacemakers and connectors. Here are several effective strategies – with concrete examples – for Asian American Christians who seek to build trust and solidarity with the Black community:

- Acknowledge Shared Struggles and Reject Divisive Myths: Start by openly recognizing the common experiences of marginalization that Asian and Black Americans share, while also acknowledging differences. Dismantle the “model minority” myth in your church circles – explain how it was a wedge strategy invented in the 1960s to claim that America isn’t racist by pitting Asians as the “good minority” against “bad” minorities. Educate others that this myth is “historically used to distinguish Asian Americans…from African Americans,” and that it ignores the racist policies that benefitted one group over another. Point out, as Professor Peter Cha notes, how some Asian immigrants prospered because of biased U.S. immigration laws, whereas Black Americans faced centuries of enslavement and segregation – so it’s wrong to compare the outcomes without context. By rejecting false comparisons and affirming that both communities have suffered under white supremacy (just in different ways), you set a truthful foundation. This honesty creates respect: it shows Black Christians that Asian Americans aren’t naive about racism or their own community’s prejudices. It also frees both groups from resentment so they can unite against the real enemy – systemic racism – rather than each other. In practice, this might involve a workshop or sermon series on race in America, highlighting how anti-Asian exclusion laws and anti-Black slavery/Jim Crow share a connected history (one Black pastor even noted how an 1850s anti-Chinese ruling paved the way for the infamous Dred Scott case denying Black citizenship). Such education helps everyone see that “white supremacy has often treated us in similar ways” and that our communities’ fates are linked, which is the first step toward genuine solidarity.

- Listen Humbly and Learn from Black Experiences: Trust-building begins with relationships. Asian Americans can take initiative to listen to Black brothers and sisters – to their stories of pain, hope, and faith – without immediately trying to compare or interject their own experiences. This kind of empathetic listening can happen in small group settings, one-on-one conversations, or public forums. For example, Pastor Juliet Liu (a second-generation Chinese American) observed that when women from Black and Asian American communities share their experiences and “hear the pain and the resilience in one another’s stories,” it creates “true solidarity…that frightens white supremacy.” Make space in church gatherings for Black congregants to voice what they’ve endured and what they desire, and affirm their testimony. Asian Americans should approach these conversations as learners, not as experts – even if you yourself have experienced racism, recognize that anti-Black racism has its own particular history and trauma. Show genuine concern: attend Black-led Bible studies or conferences on racial reconciliation (even if they’re outside your comfort zone), and simply be present. Over time, consistent, compassionate listening communicates, “I see you and I care.” That goes a long way to countering any wariness. It’s often noted that the Black community has encountered outsiders who want their “input” but don’t stick around; by contrast, Asian Americans can build trust by being consistent friends in both celebration and crisis. In ecumenical settings, volunteer to join interracial prayer groups or book clubs (e.g. reading a work by a Black theologian or Christian author) – this not only educates but also deepens personal bonds. Remember, trust is earned through time and sincerity, so commit to a long-term journey alongside Black colleagues in ministry.

- Address Anti-Black Attitudes in Your Own Community: A crucial part of being an ally is “cleaning house” within your own ranks. Asian Americans should lovingly but firmly confront anti-Black sentiments that may exist in their families, churches, or ethnic enclaves. This might involve correcting stereotypes, challenging jokes or comments, and teaching on God’s heart for racial unity. The AACC has explicitly called out the need to examine how “Asian Americans have served as a wedge against our Black and Brown peers” in the past. A younger generation of Asian American Christians is now pushing their immigrant parents’ churches to repent of indifference or prejudice toward Black Americans. One practical idea is hosting a workshop on anti-Black racism for your Asian fellowship, possibly in partnership with a Black church. Share from Scripture (e.g. James 2’s warning against favoritism) and also from history – for instance, discuss how some Asian American storeowners or community leaders have had tensions with Black communities (like in 1990s L.A.), and why Christians must take a different path of reconciliation. Encourage Asian Americans to see standing up for Black lives as part of standing up for truth and justice. It’s important to frame this not as an exercise in guilt, but as discipleship: we all have biases to unlearn as we conform to Christ. When Black Christians see Asian Americans actively wrestling with and rooting out anti-Black racism among themselves, it builds trust. It signals that you are a safe partner who will not betray them when racial tensions heat up. For example, after an Asian police officer stood by during George Floyd’s murder, many Asian American Christians publicly lamented his inaction as “a perfect representation of Asian American complicity” and urged their communities not to be bystanders. Such honest self-reflection showed Black onlookers that Asian believers are serious about confronting sin, even in their own community, for the sake of justice.

- Show Up and Stand in Solidarity: Solidarity is spelled in part as presence. One way Asian Americans build credibility as allies is by consistently showing up when the Black community is hurting or mobilizing. Don’t wait for an invitation; if there’s a prayer vigil, a protest, a community forum, or a service project addressing racial justice, gather a group from your Asian American church to attend in support. In recent years, we’ve seen powerful examples of this: Asian American Christians marching shoulder-to-shoulder with Black Christians to protest police brutality, and in turn, Black congregations rallying around Asian Americans during a spike in anti-Asian hate. These acts of showing up are noticed. They communicate love in action. If you are in a predominantly White church context, you might be the one to encourage your congregation’s involvement in a traditionally Black-led event (for instance, a Martin Luther King Jr. Day service or a local NAACP Faith Alliance). Your willingness as an Asian American to participate can inspire others across racial lines. Consistency is key: don’t let solidarity be a one-time “photo op.” Continue to follow through. Perhaps your church can “adopt” a sister relationship with a Black church – attending each other’s major events, supporting each other’s social outreach. When a crisis happens (e.g. another police shooting or a racist incident), reach out immediately with condolences, prayers, and offers of practical help (just as Black church friends did for Asians after the Atlanta tragedy). In predominantly Black or White church settings, being present also means standing up against anti-Black injustice even when your own community isn’t directly affected. By protesting the evil of racism as a sin that grieves God, you demonstrate that you’re not in this for self-interest alone but out of Christian conviction. Over time, the Black community will come to see you as genuine comrades who “have their back.” That trust, once formed, allows for deeper collaboration and mutual support. As one Asian American Christian leader noted after participating in Black Lives Matter protests, “I saw that Asian Americans can be unexpected allies that catch people off guard” – in a good way. Your presence can be a pleasant surprise that paves the way for new friendships.

- Partner in Ministry and Service Projects: Building solidarity is not only about reacting to crises – it’s also about proactively working together on shared projects. Asian American Christians can volunteer alongside Black churches in community development efforts (and vice versa). For instance, if a Black church is hosting a neighborhood tutoring program or food pantry, a team from a nearby Asian church can join regularly to serve. Serving together forges camaraderie as you labor toward a common goal. It also shows that your concern isn’t limited to “racial issues” narrowly defined, but extends to the real-life needs of each other’s communities. Likewise, invite Black Christians to join initiatives your church leads – maybe a healthcare fair in an Asian immigrant community or an evangelistic outreach – not as token guests, but as partners and advisors. Co-sponsoring events like racial reconciliation workshops or multiethnic worship nights is another strategy. By planning and leading together, Black and Asian American believers practice shared authority and trust. One concrete example is the pulpit swap mentioned earlier: Pastor Chang in Seattle routinely invites Black pastors to preach at his Chinese American church, and in exchange, he might speak at their church or they collaborate in other ways. These exchanges break down the silo mentality (“that’s your church, this is ours”) and foster a sense of one kingdom community. Additionally, joint small groups or prayer meetings can be formed around topics like Justice in Scripture or healing racial trauma. Asian Americans can facilitate mixed groups where participants from Black, Asian, and other backgrounds study, pray, and fellowship regularly. The more face-to-face time spent in ministry together, the more trust deepens. It’s often in the doing – feeding the hungry, mentoring youth, advocating for policy change side by side – that stereotypes fade and genuine brotherhood/sisterhood emerges. When others in the broader church see these partnerships, it positions Asian Americans as bridge-builders who can navigate cultural differences and bring people together for the gospel’s work.

- Use Your “Bridge” Position Wisely: Asian Americans sometimes find themselves viewed as a “middle” or neutral party in Black-White racial discussions. While this has pitfalls, it can also be an opportunity to act as a bridge. In settings where there is mistrust between Black and White Christians, an Asian American voice speaking up for justice might be received in a unique way – you might be able to affirm Black concerns in a manner that a skeptical White brother can hear, precisely because you’re neither Black nor White. Similarly, you can help Black leaders understand the perspectives (and blind spots) of majority-culture Christians. To be clear, this is a delicate role – you are not a savior or a mere go-between, and you must avoid becoming a pawn for either side. But if you have earned trust with both, you can sometimes translate and mediate. For example, in a multiracial church meeting, you might gently rephrase a Black member’s passionate plea for justice in terms that connect with the biblical values a White member holds, thus building a bridge of understanding. Or you might share your personal testimony: as an Asian American, you’ve experienced prejudice (perhaps being told to “go back to your country” or worse during COVID-19), which helps White Christians grasp that racism is real, while also relating how the Black community’s much longer fight against injustice inspired you to speak out. In predominantly White churches, Asian Americans can affirm Black voices by echoing their calls for change – effectively leveraging your “insider” status with White peers to amplify what Black Christians have been saying. In Black churches, Asian Americans can show that they’re not there to treat Black issues as a sociological study; rather, you’re invested as family in Christ. By positioning yourself as a learner and ally, you build credibility to be a bridge when needed. Remember to always defer to Black leadership on issues of Black justice – being a bridge doesn’t mean taking over. It means facilitating connection, understanding, and cooperation. When done with humility, this bridge role highlights the valuable contribution Asian American Christians can make in multiracial church spaces: you can remind each side of the other’s humanity and of Christ’s call to unity.

- Amplify and Affirm Black Voices: In practical terms, being a bridge-builder also means using whatever platforms you have to lift up Black voices in the church. If you’re organizing a conference, ensure Black Christian speakers are featured (and not just on race topics, but across the board). If you lead worship, consider incorporating songs from the Black gospel tradition or multicultural worship that honors the Black church’s contributions. Publicly acknowledge the leadership and wisdom of Black pastors and theologians that have guided your thinking. For instance, an Asian-led Bible study might quote Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or Howard Thurman alongside Scripture to show how Black Christians have illuminated biblical truths about justice. On social media or church newsletters, Asian American Christians can highlight Black-led ministries and advocacy campaigns, directing support their way. Importantly, stand up against anti-Black racism whenever it appears, even in casual comments or “between the lines” decisions in church. If a Black person’s input is ignored in a meeting, you can intervene to ensure their voice is heard – sometimes it takes an ally to say, “I think we should return to the point X was making; it’s important.” These actions demonstrate solidarity in the everyday life of the church. They also model to others that Asian Americans are not seeking spotlight for themselves, but rather seeking a just and inclusive community for all. Over time, this consistent advocacy will earn trust: Black colleagues will know you truly have their interests at heart. As Michelle Reyes (a South Asian American Christian leader) points out, including Asian Americans in multiethnic church rallies and events is beneficial because it diversifies the voices for justice and “is the method by which the church will learn to grieve and lament well.” In other words, when Asian Americans add their voices alongside Black voices – not in competition, but in chorus – the entire church is enriched in its understanding of God’s heart for righteousness.

By implementing these strategies, Asian American Christians can become effective bridge-builders in racially diverse church environments. It’s about cultivating trust through humility, solidarity, and steadfast love. Each relationship built and each collaborative action taken becomes a brick in the bridge of racial unity within Christ’s church.

Key Voices, Organizations, and Resources Leading the Way

Asian American Christians do not have to navigate this work alone – there are many leaders, networks, and resources supporting racial justice engagement in the church. Here are some key voices and organizations to know, along with recommended resources:

- Asian American Christian Collaborative (AACC): Founded in 2020, the AACC is a network that equips and encourages Asian American Christians to engage in racial justice. They have organized events like the “Asian American Christians for Black Lives” march and nationwide prayer rallies. AACC produces articles, webinars, and local chapters that foster dialogue on anti-Black racism and other justice issues. (Website: asianamericanchristiancollaborative.com)

- Progressive Asian American Christians (PAAC): PAAC is an online community (started in 2016) for Asian American Christians committed to justice, inclusion, and social change. It began as a private Facebook group and has grown into a platform that amplifies progressive voices on race, gender, and sexuality from an Asian American faith perspective. PAAC often partners with other groups for workshops and offers a space for support and discussion. (Search “PAAC Facebook group” or see PAAC organizers’ writings on platforms like HuffPost.)

- Black–Asian Christian Alliance and Dialogue Programs: In various cities, there are informal alliances of Black and Asian churches. For example, in Chicago, pastors like Rev. Raymond Chang and Rev. Charlie Dates have formed friendships that led to joint events. Keep an eye out for local pastor networks or church coalitions working on racial reconciliation – these can be valuable for finding mentors and partners. Nationally, the National Council of Churches and some denominations have race relations initiatives that include Asian and Black caucuses together. One historic example is the African American–Korean American Christian Alliance in Los Angeles, which can serve as a model for community-specific coalitions.

- Key Voices and Thought Leaders: Several individuals have been at the forefront of bridging Asian American and Black Christian communities. Rev. Raymond Chang (AACC President) and Dr. Michelle Ami Reyes (AACC Vice President) are two prominent Asian American voices writing and speaking about anti-Black racism, immigrant church dynamics, and the need for solidarity. Korean American theologian Dr. Soong-Chan Rah has authored books like “Many Colors” and “Prophetic Lament” that challenge the church toward justice and lament, often uplifting Black church insights. On the Black side, leaders such as Rev. Dr. Brenda Salter McNeil (a renowned reconciliation speaker), Rev. Otis Moss III (who has explicitly addressed Black-Asian ties), and Dr. Willie James Jennings (theologian who writes on racial healing) are important voices to learn from. There are also multiracial voices like Dr. Christena Cleveland and Jemar Tisby whose work on anti-racism and church history (e.g. Tisby’s book “How to Fight Racism”) provide practical guidance. Engaging with these thought leaders via their books, podcasts, or social media can inform and inspire Asian American Christians in their journey.

- Christian Community Development Association (CCDA): CCDA is a multiethnic network of Christians (co-founded by John M. Perkins, a Black civil rights veteran) devoted to breaking cycles of poverty and racism through the local church. Many Asian American urban ministers are active in CCDA, working alongside Black and Latino Christians. CCDA conferences and chapters emphasize reconciliation, empowerment, and justice – an ideal training ground for learning cross-cultural ministry skills. Through CCDA, one can connect with like-minded believers such as Nikki Toyama-Szeto (a Japanese American who directs an advocacy organization) or Jonathan Tran (a Vietnamese American theologian who writes on Christianity and justice), among others.

- Be the Bridge: Founded by Latasha Morrison (an African American leader), Be the Bridge is a Christian organization dedicated to racial reconciliation within churches. It provides discussion group curricula, training programs, and online communities to empower people to lead dialogues about race. Asian American Christians have been involved both as participants and facilitators in Be the Bridge groups. This ministry is a great resource for structured, gospel-centered conversations on race that can be used in small groups or Sunday school classes at church. Participating in a Be the Bridge group can equip Asian Americans with language and tools to talk about race in biblical ways, and it demonstrates a commitment to standing with Black Christians in pursuing racial healing. (Website: bethebridge.com)

- Denominational Resources and Racial Justice Ministries: Many Christian denominations have offices or initiatives focused on racial equity where Asian American voices are contributing. For instance, the United Methodist Church’s General Commission on Religion and Race (GCORR) includes Asian American and Black staff working on intercultural training for churches. The Presbyterian Church (USA) has a Racial Equity & Women’s Intercultural Ministries division that supports its Asian congregations and Black congregations in joint justice efforts. Tapping into these denominational resources (if you belong to one) can provide curricula, grants, or facilitation for local church events. Even if you’re non-denominational, you can often access these materials online (for example, Bible study guides on racism, or anti-racism training modules that some Asian American churches have utilized).

- Educational and Advocacy Groups: Organizations like ISAAC (Institute for the Study of Asian American Christianity) and CAAAMC (Coalition of Asian American American Christians) produce research and host conferences on Asian American Christian engagement with social issues. Meanwhile, secular advocacy groups with Christian involvement – e.g. Stop AAPI Hate (co-founded by Dr. Russell Jeung, a sociology professor who is also a Christian) – can offer important data and recommendations. Dr. Jeung has said his work documenting anti-Asian hate is part of “living out my faith that ushers heaven to earth” by protecting the vulnerable. By partnering with such groups, Asian American Christians gain credibility and allies in broader racial justice work.

- Recommended Resources (Books & Media): To deepen your understanding and skills, consider these resources:

- “Mixed Blessing: Embracing the Fullness of Your Multiethnic Identity” by Chandra Crane (explores how mixed and Asian Americans can be racial bridge-builders in the church).

- “Return to Justice” by Soong-Chan Rah and Gabriel Salguero (traces how Christians of color, including Asian Americans, have led justice movements and how the church can return to that legacy).

- “Brown Church” by Robert Chao Romero (though about Latino Christian activism, it provides a framework of viewing justice as integral to faith, which is applicable across communities).

- “Raise Your Voice” by Kathy Khang (encourages Asian American Christians to speak up on social issues and offers practical wisdom on navigating culture and church).

- Jemar Tisby’s video series or study guide based on “How to Fight Racism” – which can be used in church groups – incorporates actionable steps summarized by the ARC acronym (Awareness, Relationships, Commitment). This can easily be contextualized for Asian American audiences as well.

- Online, check out podcasts like “Truth’s Table” (hosted by three women of color, including Asian American theologian Ekemini Uwan) or “The Reclaim Podcast” by AACC, where topics of Black-Asian solidarity are often discussed. Also, the website Intersection of Faith and Race (e.g. articles on Interfaith America or Christianity Today) regularly features stories of Black-Asian Christian partnerships and is worth following for encouragement and ideas.

By engaging with these networks and resources, Asian American Christians can draw strength, insight, and practical models for doing racial justice work in church contexts. Importantly, these connections also expand one’s personal network of mentors and peers. For example, joining an AACC webinar may introduce you to an African American pastor in your area who is looking for Asian partners in a justice initiative. Or reading a book by an Asian American Christian on racial reconciliation might spark ideas for your own church. Each voice and organization listed here contributes to a growing ecosystem of Christians committed to racial righteousness.

In conclusion, Asian American Christians have a significant and unique role to play in the pursuit of racial justice within our churches. By learning from history, stepping forward in solidarity with Black sisters and brothers, and rooting their actions in a gospel-centered vision of equality, Asian Americans can indeed be bridge-builders in predominantly Black and White settings. The work is not always easy – it requires vulnerability, patience, and courage to challenge the status quo both in one’s own community and in the wider church. Yet, as we have seen through these examples and strategies, the rewards are profound: genuine friendships across racial lines, a more credible witness for Christ’s love, and the joy of living out the “beloved community” that God intends for His people. In a time when the American church is still too often divided by race on Sunday mornings, Asian American Christians who intentionally build trust and solidarity with the Black community are modeling the kingdom of God, in which “a great multitude from every nation, tribe, people and language” worship together before the Lamb (Revelation 7:9). Their contributions – as reconcilers, advocates, and co-laborers – are helping to lead the church toward that heavenly vision, “on earth as it is in heaven.”

Through persistent justice work, compassionate bridge-building, and faithful reliance on Christ, Asian American believers can continue to strengthen the bonds of unity with Black Christians. In doing so, they affirm that racial justice is not the work of one group alone, but the calling of the entire Body of Christ – and that we truly are better together in this holy task.